The call to #EndSARS started online in 2017. The target: Nigeria’s Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS), a police unit notorious for torture and extortion. In 2020, the hashtag jumped offline and became one of the largest protest movements in Africa’s recent history. This nationwide protest was leaderless, creative, and fueled by social media. For weeks, the #EndSARS demonstrations blocked roads and drew global attention, as Nigerians demanded justice and accountability.

The government promised change, and the police inspector general disbanded SARS. Officials announced inquiry panels and pledged police reforms. But those promises collapsed quickly. Security forces cracked down violently, most infamously at Lagos’s Lekki toll gate on Oct. 20, 2020. Soldiers opened fire on protesters. They harassed journalists and arrested organizers. Many demonstrators fled the country and remain in asylum to this day.

Five years later, little has changed

Today, SARS is gone in name only. Cases of police brutality continue, oversight panels have stalled, and victims of police violence rarely see justice. In August, a journalist from the Foundation for Investigative Journalism (FIJ) was assaulted while covering a case of police extortion from detainees in Lagos.

This year’s anniversary of the Lekki toll gate crackdown underscores a painful truth: What Nigerians believed to be a turning point has instead become a reminder of how little Nigeria’s institutions can be trusted to implement change . Research shows that episodic protest events like the #ENDSARS protest as highly visible, media-friendly moments that draw attention but risk obscuring deeper problems. The remembrance of Oct. 20, 2020, shows this pattern clearly.

Silas Udenze, a scholar of social media and political movements, points out that the first anniversary centered on mourning. The second marked the rise of the “Obidient” movement. The third coincided with Nigeria’s 2023 general elections, while the fourth reflected fatigue. In my view, this fifth year has returned the spotlight to the continuing police abuses. The persistence of these cycles of violence underscores a hard truth: The problem was never just SARS. Instead, it is the weakness of the institutions designed to hold security forces accountable. And when citizens see their public institutions failing repeatedly, trust in democracy itself begins to erode.

When repression replaces reform, trust erodes

Research shows that trust in public institutions is fragile where governments repress dissent instead of delivering change. Nigerians, according to Afrobarometer data, are among the least trusting citizens in Africa when it comes to the police, the courts, and electoral authorities.

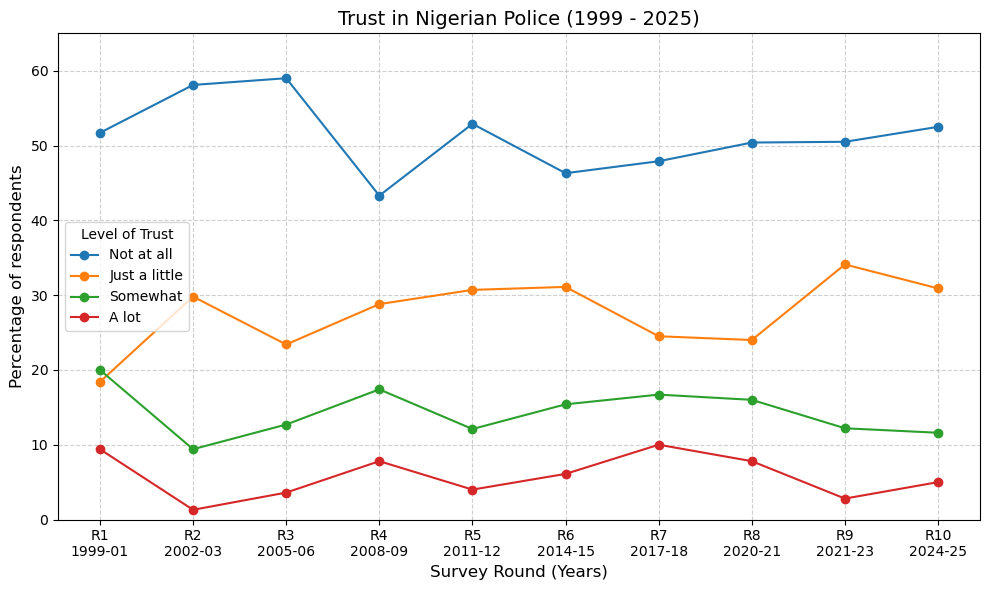

Afrobarometer surveys underscore Nigerians’ distrust of authorities. Since 1999, at least half of Nigerians have said they do not trust the police at all. Fewer than one in ten say they trust the police “a lot.” The picture has barely shifted in two decades, as the figure below illustrates. The outlook has worsened since 2020. In fact, more than 80 percent now express little or no trust in the police.

The pattern is clear. When the government responds to protests with bullets instead of actual policy changes, citizens lose faith not just in security agencies but in democracy itself. My own research on political campaigns shows that negative messaging by elites erodes trust in institutions as well as in politicians. Repression of protesters works in the same way. It signals the government is willing to apply rules unevenly, and protect power at all costs – and that accountability does not matter.

Trust, once broken, is hard to rebuild. And each new episode of abuse – from Lekki in 2020 to the assault of the FIJ journalist in 2025 – reopens old wounds.

Why it matters now

Nigeria is heading toward a pivotal election in 2027. Public confidence in the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) has already been shaken by the 2023 general elections and recent off-cycle elections. When citizens do not trust the police to protect them or the courts to defend their rights, they are less likely to believe that their elections are free and fair.

The same distrust that followed the Lekki shootings now shadows Nigeria’s elections. My research shows that political messaging plays a powerful role in shaping this trust. Negative and divisive campaign messages erode faith in elections by fostering cynicism and amplifying perceptions that politicians and the institutions overseeing them cannot be trusted. These effects are strongest where electoral management bodies lack autonomy and transparency. In stronger institutions, negativity does less damage. In weaker institutions, negative messaging causes more harm when public suspicion and voter disengagement are already high.

As political scientist Nicholas Kerr argues, democratic legitimacy depends on capable, transparent, and independent election bodies that sustain public confidence even under pressure. Five years on, the lessons from #EndSARS are clear: Protests are not a threat to democracy. They are a democratic resource. What weakens democracy is the government’s refusal to translate protest into policy changes that address institutional failures and rebuild public confidence in Nigeria’s democratic system.

Kelechi Amakoh is a 2025-2026 Good Authority fellow.