On Oct. 29, Tanzanians will elect a president, members of the National Assembly, and ward councillors. But key opposition leaders won’t be on the presidential ballot. Tundu Lissu, the main opposition politician, remains in custody, facing treason charges. His party, CHADEMA, has been disqualified from participating in the election. The Alliance for Change and Transparency’s (ACT-Wazalendo) nominee, Luhaga Mpina, was also barred.

In Côte d’Ivoire, multiple challengers were ruled ineligible months ahead of the Oct. 25 election. And in Burundi, opposition leaders were sidelined in the lead-up to the country’s June 2025 legislative and local contests, limiting space for competitive politics.

These aren’t isolated incidents. Across several African countries, ruling parties are shaping elections long before election day. They’re using courts, commissions, and campaign rules to decide who can run, who can speak – and who gets silenced.

What is pre-election manipulation?

Unlike ballot box fraud or vote counting problems, pre-election manipulation is about controlling who gets to run for office, and campaign. Tactics include biased media coverage, abuse of government resources, disqualifying candidates, setting strict eligibility rules, and creating hurdles that make it hard for opposition figures to participate. By limiting the field early, ruling parties reduce competition while keeping the appearance of an election.

In many African countries, elections are decided as much by who is allowed to run as by how the final votes are counted. By narrowing the field early, ruling parties reduce competition while maintaining the appearance of a formal democratic process. Nic Cheeseman and Brian Klaas describe these tactics as part of a broader authoritarian strategy in their book, How to Rig an Election. They show how incumbents manipulate the entire electoral cycle, using legal barriers and selective enforcement to suppress opposition.

Limiting who can run reshapes campaigns – and voter choice

Restricting who appears on the ballot does more than reduce voter choice. It limits how opposition parties organize and reach voters. In Africa, where campaigns rely on public rallies, disqualification denies opposition candidates both ballot access and the right to hold large public events.

Even when opposition figures remain in the race, a hostile political environment will constrain where and how they can campaign. In Tanzania, for example, CHADEMA relies on lone organizers who build support through personal networks, while ACT-Wazalendo has turned to social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter) to mobilize and communicate with supporters when traditional campaign avenues are blocked.

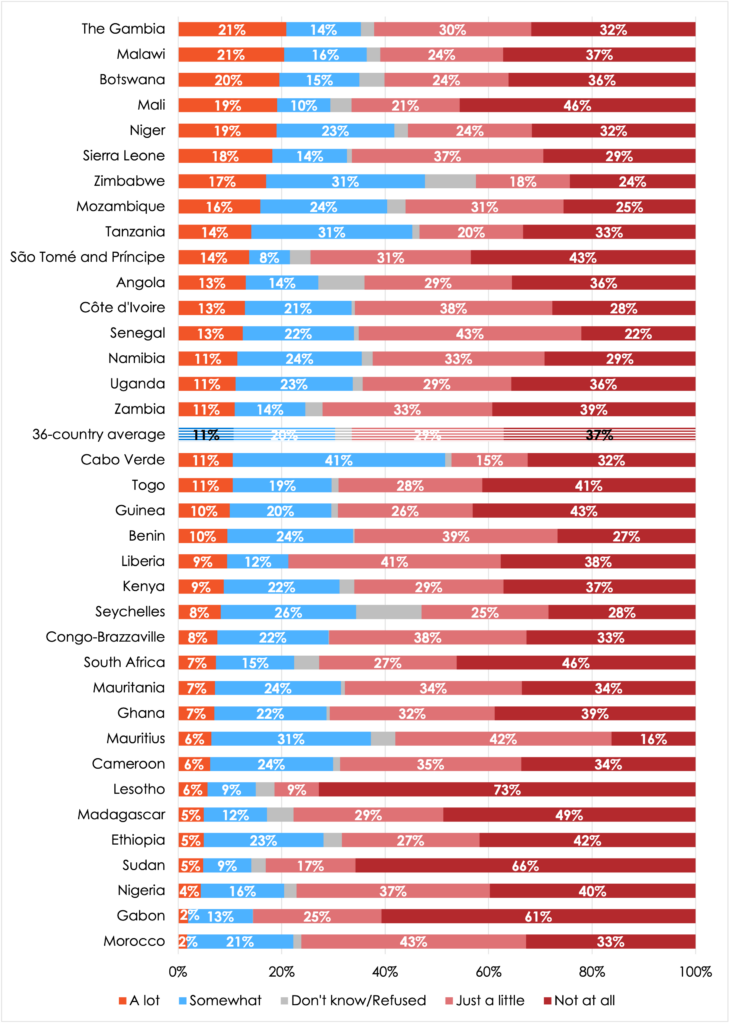

This matters even more in countries where public trust in opposition parties is gaining traction. In Tanzania, for example, 45% of respondents in Afrobarometer’s Round 9 survey (2021-2023) say they trust opposition parties “somewhat” or “a lot.” This is above the average for the 36 African countries surveyed. Afrobarometer surveys in Côte d’Ivoire show similar signs that more voters see opposition’s credibility rising. Rather than reflecting a lack of trust, the recent wave of disqualifications may signal the government’s response to growing public support (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Trust in opposition parties across 36 African countries

Why this matters for elections

As Tanzanians head to the polls on Wednesday, the results may already be tilted. With top opposition candidates disqualified or detained, the ruling party has shaped the race before any ballots are even cast. But this is not just a Tanzanian story. It reflects a broader pattern across the region, where authoritarian regimes narrow the field early to weaken challengers while preserving a democratic façade.

Research shows that limiting who can run affects not just the candidate list but also how campaigns unfold, how opposition parties organize, and how voters engage with the democratic process. In settings where public trust in opposition parties is already low and campaign rules are unevenly enforced, ruling parties can shape both the field of competition and the public narrative long before voters arrive at the polls.

Kelechi Amakoh is a 2025-2026 Good Authority fellow.