In November 2025, Guinea-Bissau’s President Umaro Sissoco Embaló announced he had been deposed, days after the Nov. 23 elections. The announcement shocked the nation and drew immediate controversy.

The opposition party, Social Renewal Party (PRS) accused Embaló and his party, Madem-G15, of blocking their candidate Fernando Dias from being declared the winner. And election observers including former Nigerian president Goodluck Jonathan questioned the credibility of the coup claims. Instead, he suggested Embaló had fabricated the crisis to avoid announcing an opposition victory.

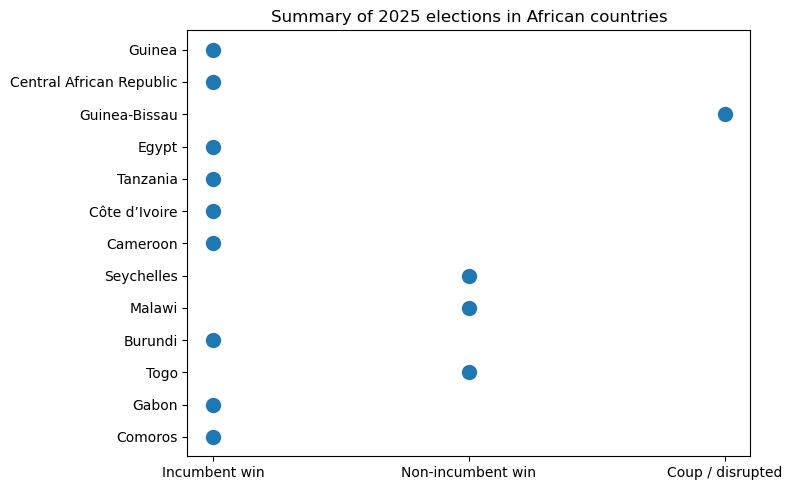

Across Africa, post-election disputes, opposition stifling, and fragile democratic institutions continue to challenge fair political competition. Contested elections last year highlighted five important takeaways:

1. Incumbents continue to thrive

Elections throughout 2025 tested the strength of incumbent candidates. The degree of control over electoral commissions, courts, and security forces often mattered more than campaign platforms. In multiple cases, incumbents or transitional leaders won by large margins. For example, President Paul Biya was re-elected to lead Cameroon in October, extending his decades-long rule, despite considerable controversy. Similarly, President Alassane Ouattara secured a fourth term in Côte d’Ivoire’s October election. He won by a wide margin despite low voter turnout and political unrest.

2. Post-coup elections are all about legitimacy

In 2025, three elections in West and Central Africa were shaped by military intervention, each in a different way. Elections in Gabon and Guinea followed earlier coups (in 2023 and 2021, respectively). In Guinea-Bissau, a coup disrupted the Nov. 23 elections before the results were released.

Gabon’s April elections were explicitly about the legitimacy of the coup leadership. Brice Oligui Nguema, the military leader who came to power after the 2023 coup, ran for president amid widespread debate over his eligibility. His campaign emphasized national unity and post-coup reconstruction. It used the slogan “We Build Together” to frame the vote as a civilian reset rather than a continuation of military rule.

One video, for instance, shows Nguema dancing at a campaign rally to the 1990 hit “(I’ve Got) The Power” by Snap!, signaling his confidence in winning Gabon’s election.

3. Several incumbents managed to stifle the opposition

In countries such as Tanzania, Côte d’Ivoire, and Burundi, incumbents sidelined opposition leaders in the run-up to elections. This suppression limited who could run for office, shaped how candidates could conduct their campaigns, and constrained opposition organizing.

As I wrote ahead of the Tanzanian elections in October, the government blocked major opposition leaders from running and limited their ability to campaign.

These actions demonstrate how authoritarian leaders can win elections without stealing votes on election day. Instead, they shape the outcome long before people turn out to vote by controlling who is allowed on the ballot, who can campaign freely, and the messages voters are able to hear. By the time ballots are cast, the election may appear orderly, but any real competition has already been removed.

4. Negative campaigns thrive where institutions are weak

In countries where electoral institutions are already fragile, negative campaigning further weakens public trust in electoral outcomes. Ahead of Malawi’s September election, several incidents of negative campaigning emerged. Former president Peter Mutharika accused Malawi Congress Party (MCP) Secretary General Richard Chimwendo Banda and President Lazarus Chakwera of intimidation in the Central Region. Banda fired back, urging Mutharika to “clean his own house first” and pointing to alleged cases of violence involving members of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). This prompted the intervention of the Malawi Electoral Commission (MEC) chair, Justice Annabelle Mtalimanja.

5. Even when flawed, elections still matter

Elections across Africa remain a vital way to organize, mobilize, and gain international support. However, many of last year’s elections fell short of democratic norms and expectations.

As political scientists Jaimie Bleck and Nicolas van de Walle argue in their book on elections in Africa, regular elections in sub-Saharan Africa have become “the default option of politics.” Rather than viewing elections only as mechanisms for democratic accountability, the authors emphasize elections as moments of temporary political fluidity. These periods of uncertainty allow citizens and political parties to mobilize, contest power, and signal legitimacy, even if these moves rarely produce lasting democratic change.

Recent elections illustrate this clearly. In Cameroon, Biya has been in power for over 40 years, winning multiple terms despite ongoing controversies over term limits. Yet each election cycle still reshapes political behavior. Opposition coalitions reorganize, the risks of protests rise, and external governments and institutions shift how they engage with the regime.

In Côte d’Ivoire, Ouattara secured a fourth term despite low turnout – but this election still mattered politically. It intensified elite bargaining within the ruling coalition, constrained opposition strategies, triggered localized protests, and prompted renewed scrutiny from regional and international observers.

These cases reflect Bleck and van de Walle’s central insight that elections matter in Africa because they keep political competition alive and make it harder for leaders to rule without challenge.

Kelechi Amakoh is a PhD candidate in political science at Michigan State University, and a 2025–2026 Good Authority fellow. His research focuses on elite communication and how it shapes voter perceptions and democratic attitudes in multiethnic societies.