Four things to watch in Uganda's 2026 election

January 16, 2026 - Kelechi Amakoh

On Jan. 29, 2026, Yoweri Museveni will mark 40 years in power. But before that controversial milestone, more than 21 million Ugandans are expected to vote in the Jan. 15 elections. Museveni faces eight other presidential candidates cleared by the Electoral Commission of Uganda to run in this year’s elections.

In 1986, the New York Times described Museveni as a rebel, not a statesman. In 2026, he’s one of Africa’s longest-serving elected leaders. Four decades in office raise hard questions about power and about the promises that once defined his rule.

Many analysts expect Museveni to win reelection, but this election is about more than extending the president’s time in office. It is about how Ugandans read their own political history. Will voters justify continuity as stability? Or will voters give a clear signal for generational change? In many ways, Ugandans will be deciding what 40 years of leadership should mean for the country’s future.

Here are four things to note in Uganda’s 2026 elections:

1. Museveni has reshaped how Ugandans vote – and how they see elections

After nearly four decades in power, Museveni has solidified his position, and shaped how Uganda holds elections. His message is conveyed not only through campaign slogans, but through state institutions, security narratives, internet shutdowns, and public-order controls that frame continuity and stability as national priorities.

Ahead of the Jan. 15 election, for example, the government restricted information flows by banning live broadcasts of protests and limiting coverage of what it calls “unlawful processions.” Critics say these measures narrow public scrutiny of the incumbent leadership and constrain the ability of opposition parties to mobilize. Many now see this election as a referendum on order, rather than an open and democratic competition.

Campaign rhetoric in recent weeks reinforce that framing in campaign rhetoric. Museveni’s slogan – “Settle for the Best, Museveni is the Best” – emphasizes continuity, while opposition leaders offer competing visions. Robert Kyagulanyi (more commonly known as Bobi Wine) promotes a “New Uganda” under “People Power, Our Power,” and Mugisha Muntu campaigns on “Change You Can Trust.”

Museveni’s dominance rests on institutional change. His administration removed term limits in 2005, and age limits in 2017. As political scientist Boniface Dulani notes, Uganda reflects persistent personalist politics, where informal power networks outweigh constitutional rules.

2. The opposition faces heavy pressure – and the erosion of hope

Just four years old when Museveni came to power in 1986, Wine, under the National Unity Platform campaign party, now leads the opposition. But the confidence of opposition candidates in elections as a route to change has faded. In December 2025, Wine captured that mood when he told a CNN reporter, “This is not an election. This is war.”

The opposition is under heavy pressure. Arrests, disrupted rallies, and intimidation by government security forces have raised the costs of participation and reinforced perceptions of a closed political space.

Yet opposition candidates maintain their efforts to get on the ballot, and vie for public office. Researchon authoritarian regimes shows why: Participation in elections preserves visibility, signals legitimacy, and ensures political survival. In Uganda, campaigning has become a strategy of endurance, rather than an expectation of being voted into office.

3. Ugandans saw repression and intimidation before election day

On Jan. 9, the United Nations Human Rights Office warned about widespread repression in Uganda’s election campaign. Opposition candidates, journalists, and human rights defenders faced arrests, suspensions, detentions, and restrictions that limited where and how they could campaign.

4. The Electoral Commission of Uganda faces scrutiny over its enforcement efforts

The Electoral Commission of Uganda, chaired by Justice Simon Byabakama, issued warnings against illicit campaign activities, including negative campaigning and hate speech. At the same time, the commission has faced growing public scrutiny over how consistently and impartially electoral rules are enforced in practice.

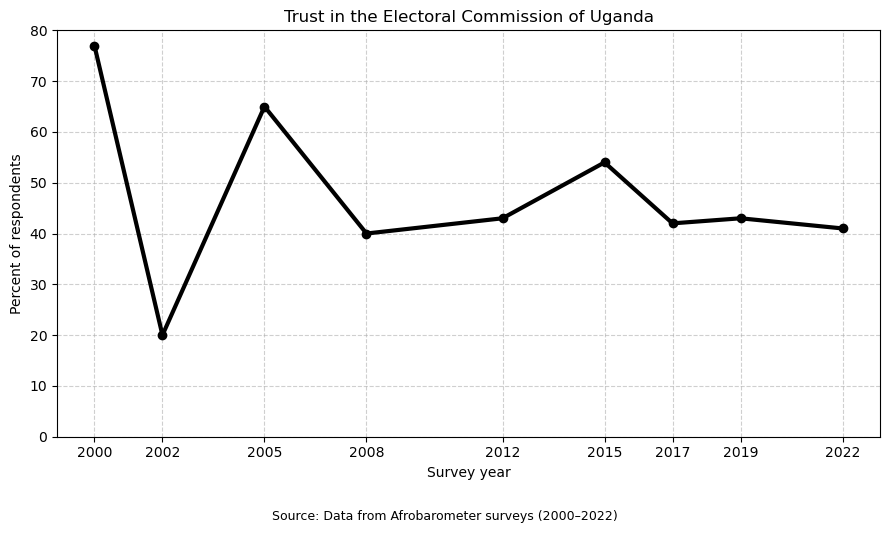

According to Afrobarometer data, only a minority of Ugandans have expressed high levels of trust in the Electoral Commission in recent years (see figure). That skepticism raises the stakes for transparent enforcement and equal treatment of political parties and individual candidates.

Kelechi Amakoh is a PhD candidate in political science at Michigan State University and a 2025–2026 Good Authority fellow. His research focuses on elite communication and how it shapes voter perceptions and democratic attitudes in multiethnic societies.