Why elected leaders began to speak more positively about immigration 75 years ago

September 29, 2025 - Dr. Eric Gonzalez Juenke

MSU Political Science Associate Professor Eric Gonzalez Juenke is a fellow with Good Authority. This article was published here on Sept. 22, 2025.

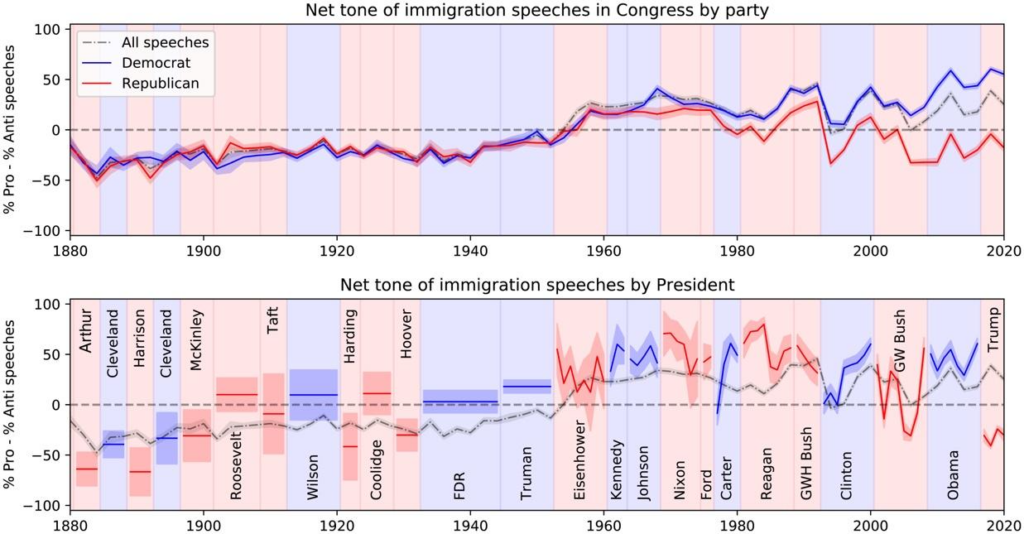

Most Americans alive today grew up with presidents who spoke positively about immigration. We know this because of one of the most informative political figures ever published. The graphic, from a 2022 article by Stanford University scholars Dallas Card, Serina Chang, Chris Becker, and Dan Jurafsky, captures the overall tone of 140 years of presidential and congressional speeches about immigration. Looking at history this way helps explain how the United States changed its perspective on this charged topic over time.

The authors quantitatively examined roughly 200,000 congressional and presidential speeches about immigration between 1880 and 2020 to capture the overall tone of the speech: pro-immigration, anti-immigration, or neutral. The red and blue lines represent the overall “pro” minus “anti” tone in these speeches. Red lines denote the overall tone of Republican speeches and blue lines mark the overall tone of Democratic speeches. The historical data reveal much about America’s recent past – and current polarization.

This history is marked by three distinct periods. The first covers the years prior to the beginning of the Cold War in the late 1940s. This period – and the impact of the 1924 Immigration Act – is described in an earlier post I wrote for Good Authority.

What prompted the change in rhetoric?

What’s notable, as the figure here shows, is that neither Congress (shown in the top half) nor presidents (see the bottom half) shifted their rhetorical tone either before or just after the historic 1924 legislation.

During and after World War II, however, public speeches about immigration in the United States adopted a more conciliatory tone. Congress and U.S. presidents started to wage an ideological battle against communism and totalitarianism, forcing them to reconcile with a restrictive and race-based immigration status quo. The 1920s immigration quota system was characterized as “offensive to our allies and potential allies throughout the world and a slur to millions of our citizens.” President Harry Truman explicitly referred to this global ideological fight in a veto message to Congress regarding the 1950 McCarran Internal Security Act. The act tightened immigration restrictions at a time when presidents sought to expand executive power over domestic policy areas by invoking national security needs. Truman remarked:

The U.S. as a haven for political refugees

Cold War maneuvering in the international order opened new ground for a propaganda fight over freedom, authoritarianism, and the eugenics movement that had defined the previous immigration regime. Truman, along with presidents Dwight Eisenhower, John F. Kennedy, and Lyndon Johnson, was acutely concerned about the U.S. image abroad. Offering a strong alternative to communist and authoritarian countries became an important part of U.S. foreign policy, along with the ability to provide asylum to refugees from these countries. This was the era, for example, when the families of Senator Ted Cruz (R-Texas) and Secretary of State (and former Florida senator) Marco Rubio sought refuge from Cuba. The strategic idea behind a more open refugee asylum policy was to “…embarrass communist states, and in some cases was used with the intent of frustrating the consolidation of communist revolutions and hopefully destabilizing nascent communist governments.”

A closer look at two important pieces of immigration legislation

As a result, this era produced two of the most transformative pieces of immigration legislation in the 20th century. The 1965 Hart-Cellar Act changed the immigration system from one that relied on national origin to a system that focused on immigrant skills and family reunification. As he signed the immigration bill into law at the Statue of Liberty, President Johnson commented on the Cold War significance and specifically mentioned both Vietnam and Cuba. The ideological importance of the act was plain in Johnson’s remarks:

Two decades later, the 1986 Simpson-Mazzoli Act would have an equally significant impact. This legislation represented the still-positive Cold War immigration sentiment – but also signaled the coming end of this era. Initiated under President Jimmy Carter and signed into law by Ronald Reagan, the law created a pathway to citizenship for an estimated 3 million undocumented immigrants. It also set up a new enforcement regime to tighten the U.S. border and punish businesses that hired undocumented workers.

America shuts the door again

The end of the Cold War destabilized the bipartisan national security coalition on the topic of immigration, leading to polarization in immigration rhetoric. Pro-immigration Republicans like President George W. Bush and Senator John McCain (R-Ariz.) remained vocal into the 2000s. Yet the waning need for Cold War asylum policies opened space for a return to more negative immigration rhetoric. And both national parties were in the midst of a geographic and ideological realignment around issues of civil rights, race, and ethnocentrism. Indeed, the success of pro-immigration policies during the Cold War created a political backlash in the 1990s in California to limit services for undocumented immigrants. The negative rhetoric against immigration then expanded exponentially after the attacks of September 11, 2001.

This third era runs from the early 1990s to the present. In the figure above, the increased party polarization in the past two decades is quite clear, in both presidential and congressional speeches. Whether political elites recognized it or not, the time of bipartisan dealmaking on U.S. immigration policy was ending. That is the period we will examine next. Stay tuned for the third installment of this series.

Eric Gonzalez Juenke is a 2025-2026 Good Authority fellow.